Some recipes don’t change across the years; others do. As tastes and preferences change, recipes are updated. In other cases, lack of availability of an ingredient might lead to tweaking of an old recipe. Also, for commercially-prepared foods, government regulations can affect their composition. Last week I was amazed to discover that the government regulated French Dressing for many years.

Some recipes don’t change across the years; others do. As tastes and preferences change, recipes are updated. In other cases, lack of availability of an ingredient might lead to tweaking of an old recipe. Also, for commercially-prepared foods, government regulations can affect their composition. Last week I was amazed to discover that the government regulated French Dressing for many years.

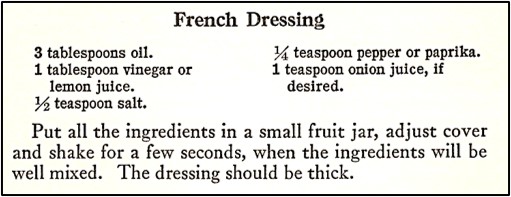

On January 13, the Wall Street Journal had an article titled “The U.S. Federal Government Deregulates French Dressing.” The government established the standard for French Dressing 72 years ago, and “according to the original 1950 standard, a French dressing should include vegetable oil, and a vinegar and/or lemon or lime juice, and could be seasoned with ingredients such as salt, sugar, tomato paste or puree, and spices such as mustard are paprika.”

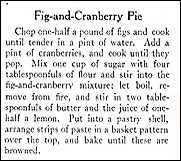

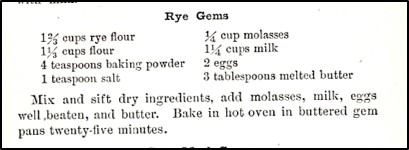

This article made me remember the many French Dressing recipes that I’ve seen in hundred-year-old cookbooks over the years, and how those recipes differed from today’s seemingly ubiquitous creamy orange dressing. Back then the dressing was often more of a vinaigrette. Here are two French Dressing recipes from 1922 cookbooks:

Source: Good Housekeeping’s Book of Menus, Recipes, and Household Discoveries (1922)

Source: Good Housekeeping’s Book of Menus, Recipes, and Household Discoveries (1922)

I made the French Dressing in the photo using the first recipe.

Several years ago, I did a post with a recipe for Endive Salad with Homemade French Dressing that contained three 1912 French Dressing Recipes. Here are those recipes:

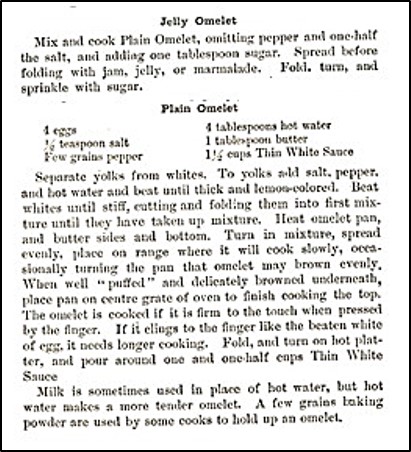

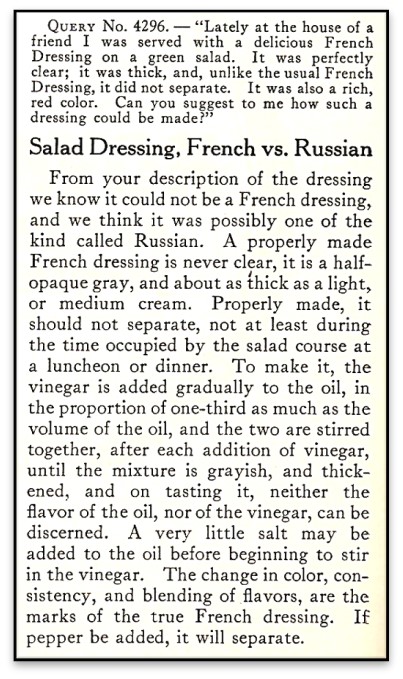

And, here is a 1922 magazine article that responds to a reader’s question about French Dressing. The response differentiates between French Dressing and Russian Dressing -though it is mostly focused on French Dressing:

Whew, my head is spinning. Who would have guessed that for a least a hundred years people have been giving lots of thought to exactly what comprises French Dressing?