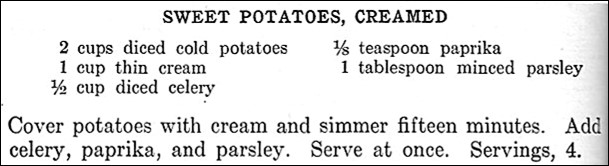

I recently came across a hundred-year-old recipe for Potato Biscuits, and decided to give it a try. The biscuits were soft and tender. This recipe is a great way to use up leftover mashed potatoes.

Here’s the original recipe:

This recipe calls for using the Crisco brand of shortening. That’s because the recipe was published in a 1924 promotional cookbook for Crisco. When I updated the recipe, I changed it to just “shortening” since any brand would work. I used all-purpose flour rather than pastry flour when I made this recipe, and it worked fine.

Here’s the recipe updated for modern cooks:

Potato Biscuits

1 1/2 cups all-purpose flour

3 teaspoons baking powder

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 cup mashed potatoes

1/4 cup shortening

approximately 1/3 cup milk, as needed

Preheat oven to 450° F. Mix the flour, baking powder, and salt together; stir in the mashed potatoes. Then cut (work) in the shortening and butter using fingers, pastry blender, or food processor. Gradually add the milk while mixing with a knife or spoon. Continue adding liquid until there is a soft dough. The amount of milk needed varies depending upon the type of flour. On a floured board, pat or roll the dough until 1/2 -inch thick. Cut with a round biscuit cutter. (I used a drinking glass as the cutter.) Place on a baking sheet, and bake for 15 – 20 minutes, or until lightly browned. Serve warm.