I can get great locally-grown produce at the farmer’s market, or I could join a community supported agriculture (CSA) group and pick up wonderful local foods at a nearby drop point — but I dream of curated farm-fresh food coming right to my door on a regular basis. I long for the good old days. A hundred years ago families in the New York City area could get fresh fruits and vegetables from Long Island in the mail.

Here’s some quotes from a 1916 article about it.

The farm-to-family-fresh idea is Edith Loring Fullerton’s, and a very clever idea it is. Mrs. Fullerton believed that a basket of fruits and vegetables, freshly picked, sent straight from the farm would appeal to the city housewife.

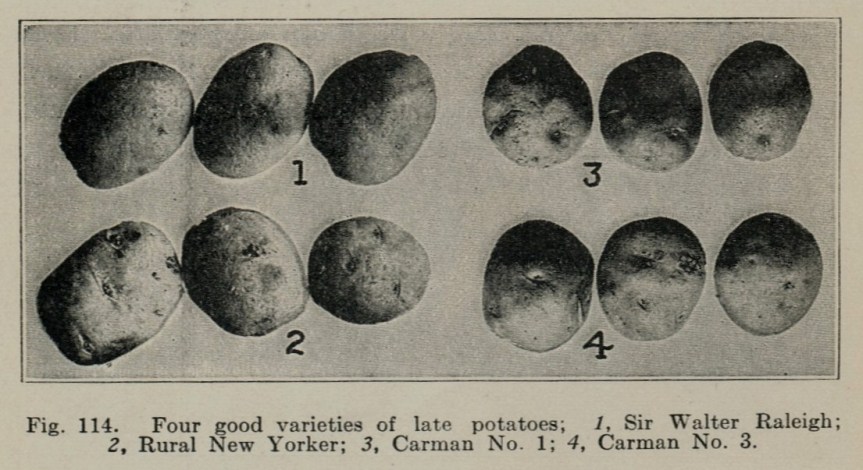

Evidently it did, for the “Home Hamper” is a great success. The hamper itself is an oblong crate twenty-four inches long, fourteen wide and ten deep; it contains six baskets and weights from thirty to thirty-five pounds. In it the housewife finds such staples as potatoes, beans, peas, tomatoes, sweet corn, soup and salad vegetables, and in season strawberries, peaches, cantaloupes, eggplants, etc.

With the parcel post the hamper idea is being rapidly taken up by woman farmers, some of them adding eggs, poultry, butter or flowers to the hamper lists.

The housewife finds that not only does the hamper reduce the cost of living, but the difference between freshly picked vegetables and those picked unripe to ripen in transit is greatly appreciated by her family.

Mrs. Fullerton is one of the vice presidents of the new cooperative organization of woman gardeners — the Women’s National Agricultural and Horticultural Association, which has for one of its objects to “bring together the producer and consumer.”

Ladies Home Journal (May 1916)

I want to think that delivery services are faster and more efficient now than in the early 1900’s but apparently parcel post packages were delivered by the U.S. Postal Service much quicker and more dependably a hundred years ago than now (at least in urban areas). Parcel post began in the U.S. in 1913, and was seen as a way for farmers to get supplies, and for consumers to get farm produce. Trains, horse-drawn wagons, and trucks quickly transported the perishable parcel post hampers into the city from the outlying agricultural areas.