Since seafood is very healthy, I try to make it several times a week, but I tend to get into a rut and make the same few recipes over and over. So when I came across a hundred-year-old recipe for Parsley Sauce, I immediately thought about making it to serve over some perch that I had in my refrigerator.

Since seafood is very healthy, I try to make it several times a week, but I tend to get into a rut and make the same few recipes over and over. So when I came across a hundred-year-old recipe for Parsley Sauce, I immediately thought about making it to serve over some perch that I had in my refrigerator.

The Parsley Sauce turned out well, and was delightful when served with the fish. It only took a few minutes to make. It is basically white sauce with chopped fresh parsley and a bit of lemon juice added. Parsley Sauce would also be tasty on meat or other foods.

My daughter called while I was working on this post, and she asked what recipe I made. I told her, “Parsley Sauce.”

She said, “Oh, that sounds so good. I went to a fancy restaurant last week and had a similar sauce on my steak.”

I said, “Really? I didn’t think that white sauce-type sauces were very popular now.”

She said, “They’re very popular. Many dishes use white sauce as a basis.”

I clearly am behind the times (which I guess shouldn’t be a surprise), but it’s good to hear that some of the foods that were common a hundred years ago are once again popular.

Here’s the original recipe:

I thought that the sauce would get too thick if I boiled it for five minutes, so I removed it from the heat just as it came to a boil and began to thicken.

I used 1/2 teaspoon of salt and a dash of pepper, and that worked well.

The old recipe gave lots of details about how to prepare the chopped parsley to ensure that any green liquid created by the chopping process was removed so that the sauce would not be discolored. The recipe called for putting the chopped parsley in a cloth and then holding it under a water faucet. Instead, I put the chopped parsley in a tea strainer and ran water over it; I then dried the parsley by putting on paper towels that I rolled and squeezed.

Here’s the recipe updated for modern cooks:

Parsley Sauce

2 tablespoons chopped parsley (Stems and stalks should be removed before chopping.)

2 tablespoons butter

2 tablespoons flour

1 cup milk

1 teaspoon lemon juice

1/2 teaspoon salt

dash pepper

Put the chopped parsley in a strainer (I used a tea strainer.), then run water over it to wash away the green liquid created during the chopping process. Gently press the parsley to remove some of the water, then put the washed, chopped parsley on paper towels. Roll the paper towels then squeeze to remove the water. Set aside.

Melt butter in a saucepan, then stir in the flour. Gradually, add the milk while stirring constantly. Continue stirring until the white sauce begins to thicken. Stir in the lemon juice, salt, and pepper. Remove from heat and stir in the parsley.

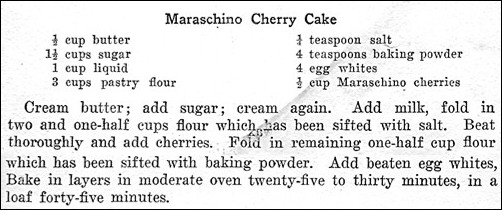

I recently had some friends over and wanted to serve a nice dessert (and, of course, I wanted to make a hundred-year-old recipe), so I pulled out my 1925 recipe books and found a lovely recipe for Maraschino Cherry Cake.

I recently had some friends over and wanted to serve a nice dessert (and, of course, I wanted to make a hundred-year-old recipe), so I pulled out my 1925 recipe books and found a lovely recipe for Maraschino Cherry Cake.

Old-cookbooks occasionally refer to recipes as “receipts.” A hundred years ago, “receipt” was already considered an archaic term. Here’s what it said in a 1925 magazine:

Old-cookbooks occasionally refer to recipes as “receipts.” A hundred years ago, “receipt” was already considered an archaic term. Here’s what it said in a 1925 magazine: