18-year-old Helena Muffly wrote exactly 100 years ago today:

Thursday, October 9, 1913: About the same as other days.

Her middle-aged granddaughter’s comments 100 years later:

Grandma was still husking corn using a hand-held corn peg. She’d been husking corn since September 25.

In the past Grandma often struggled to practice her piano lessons.—even when she didn’t seem particularly busy. On the days when she “worked for wages” and had lots to do, did she somehow still manage to find time to practice the piano?

—-

I can remember taking piano lessons for six years when I was a child—and I didn’t like practicing much either. But my goal was to be able to sight read music, so that I could just play songs that my friends might ask me to play.

I never reached that goal and ended up seldom playing the piano once I quit taking lessons.

Did Grandma also want to sight read music? I can’t remember her ever playing the piano, so my guess is that she also never reached that point.

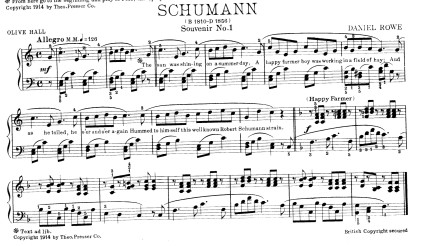

I recently was looking at an old issue of The Etude magazine and came across these tips for sight reading music. Some parts of it really resonated with me and I thought you might also enjoy it:

The Secrets of Sight Reading

Far too much attention seems to be paid to technique these days, and far too little to musicianship. There are scores of young pianists who can play the Liszt Second Rhapsody with much dash and seeming brilliance, but who cannot read a fourth grade piece at sight.

The fact is a musician is not a musician until he can read.

A knowledge of harmony is not essential to good sight reading, but it unquestionably helps very frequently a work that is peppered with accidentals will absolutely fog a student who has no knowledge of harmony, while one who has will go sailing along with the utmost abandon.

A good sight reader reads music phrase by phrase, not note by note.

There is a tendency these days among publishers and editors to avoid putting in too many signs of expression. The less gifted musician needs some signs, but too many fluster him and he ignores them altogether. Nevertheless, it is essential when reading at sight to be careful to observe all fortes and pianos, crescendos, diminuendos, rallentandos, etc. Music which has not variety of expression has no life.

Playing wrong notes is a crime in a piece that has been studied, but in sight-reading a wrong note now and then can scarcely be avoided. If you play a wrong note, however, do not stop, and do not let it get you “rattled.” Go on as if nothing had happened.

The Etude (March, 1914)

Sign. . . I wish I’d somehow learned those lessons about sight reading when I was young.

.

I’m not musical at all, but that line about reading “phrase by phrase” is so interesting to me. That’s very like reading text aloud — pausing for every word become cumbersome and difficult to follow. It’s much easier to listen to phrases.

I like it. Reading makes a good analogy.

Helena’s hands would most likely be too sore and tired for piano practice.

Makes sense to me. I also think that she probably wasn’t practicing the piano.

I wish I paid more attention to my piano lessons, too, and occasionally practiced. Isn’t it too bad our adult selves cant go back and give advice to the young selves? Not that I would’ve listened, I’m sure . . .

It’s amazing how much smarter we get as we age. 🙂

I’ve tried many times to learn, but just as with other languages, I have some sort of block – just can’t seem to get it.

I know the feeling. I haven’t tried to play the piano in years, but I think that I had some kind of block when I was a kid.

I took piano for about 4 years. But I always wanted to play by ear, and never mastered that!

I bet that a lot of people wish they could play by ear. i wonder why piano teachers don’t seem to focus on trying to teach that skill.

This was a thought provoking post for me. My daughter did up to her Grade 6 piano lessons. She could play pretty okay and passed her exams in single attempts. But somehow, the passion for music never caught on and as soon as she stopped her lessons because of pressure from studies, she just turned her back to the piano for good. Sad but true. What brings about such behaviour I wonder?

Shakti

I think that many parents (including mine) could tell the same story. I don’t have an answer for your question–but hopefully your daughter will come back to the piano and play it for enjoyment as an adult.

I never learned to “read” music even though I played the flute in the high school band. What a shame.

It’s too bad that young people often are unable to successfully transition to playing music for enjoyment as an adult.

‘One isn’t a musician until they can read’ was in the quote. I understand that. We watched our son go through learning to play clarinet, switch to sax, and play in the state champion of Iowa high school band, and college bands. His skill as a musician grew with him.

He inspired me to learn to play electric guitar. I did. I can’t read music. But, I can put on about any music, especially blues, and play along. I guess I don’t qualify as a musician. But, I sure get a lot of fun and satisfaction out of it several times a week.

Maybe I should take lessons and learn how to read.

What an awesome story! My husband often says that he’d like to learn how to play the guitar–your story is very motivating that he might be able to successfully do it.

He can do it. Help him get started.

Jim, if you are following music, you are READING something, even if it is not the printed symbols on the page. You have picked up this “knowledge of harmony” the author of the article was talking about. There is a definition of “literate” you shouldn’t forget: having a good knowledge and understanding of a particular subject.

I think you’re right. I read and respond by listening instead of notes on paper. I will keep learning, no matter what. It’s too fun to stop that.

I took guitar lessons as a teen. I had to quit when we moved and had promised myself that I would continue to play. I didn’t. I tried again a few years ago, but now I have arthritis in my hands and again I gave up. Both of my kids played instruments, but both have sadly also given them up. I didn’t set a very good example that way.

Sometimes things just happen that way. Arthritis can be so painful–it sure creates constraints on a what person can do..

reading notes is amazing to me. I have a friend who can’t read a note but he plays by ear; piano, banjo, guitar…once I asked if he knew a certain song and he said no, but sing a few lines and I did and he began to play it on his guitar!

Wow, I’ve very envious of people who can play by ear.

do you play?

The 1914 article is very interesting, I wonder what todays professional musician would think about this advice.

Yes, it would be interesting to know.

Nostalgic reminder of the days when I could do a moderately good job of sight reading. Not so any more. Sigh …

I’m impressed that you could once do it. I’ve never had that skill.

I came from a family of “ear” musicians — my father and brother can hear a song once, and then play it (with all the harmony). Neither of them can read music.

I think that for some people, music-making is located somewhere other than in the “reading” part of the brain.

I think you are right. Unfortunately, I didn’t inherit whatever gene is needed to be an “ear” musician.

I only got it corner of that gene, and found it somewhat easier to sight-read than to play by ear. They’re definitely better musicians than I. I had to work my tail off; for them it came almost without effort.

I really admire people who can read music, it just seems like goobley-goop to me. I learned folk guitar a while back but just play by ear, I also should practice a lot. I never have enjoyed playing in front of people

I guess that I never actually enjoyed playing in front of people, but I always wanted to enjoy it. Maybe I should instead have just focused on playing music because I enjoyed it.

Reminds me of piano lessons when I was young. I still sit down and play every once and a while and the ability to sight read comes in handy. I can read the music well, it is translating it to the fingers that is the problem 🙂

It’s awesome that you still play occasionally–though I’m sure it’s frustrating when it isn’t translated to your fingers exactly as you intended.

How I relate to “reading the music well” and wishing my fingers would follow!

I think the way to become a better sight reader is to join a rock and roll band and get good at playing I, VI, IV and V7 chords by ear in every key. Then, when you go back to printed music, all those accidentals are good old friends you’ve played with before. Come to think of it, all those finger excercises — scales and chords in every key — were based on the same principle. But not NEARLY so fun as playing rock and roll!

Interesting. . . I never liked scales, but this is starting to sound like fun. 🙂